The state of mental health in America is in crisis and was in crisis before the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the National Institutes of Health, pre-pandemic:

- 1 in 5 Americans suffered from a mental disorder each year,

- 1 in 17 suffered from a serious mental disorder each year, and

- there was a 35% increase in suicides in the past 15 years with suicide being the second-leading cause of death between the ages of 10 and 34.

The pre-pandemic statistics for our children are more troubling as:

- 5% of adolescents aged 13-18 had any mental disorder, and

- of adolescents with any mental disorder, 22.2% had severe impairment. (Source for all statistics: National Institutes of Health Mental Health Information)

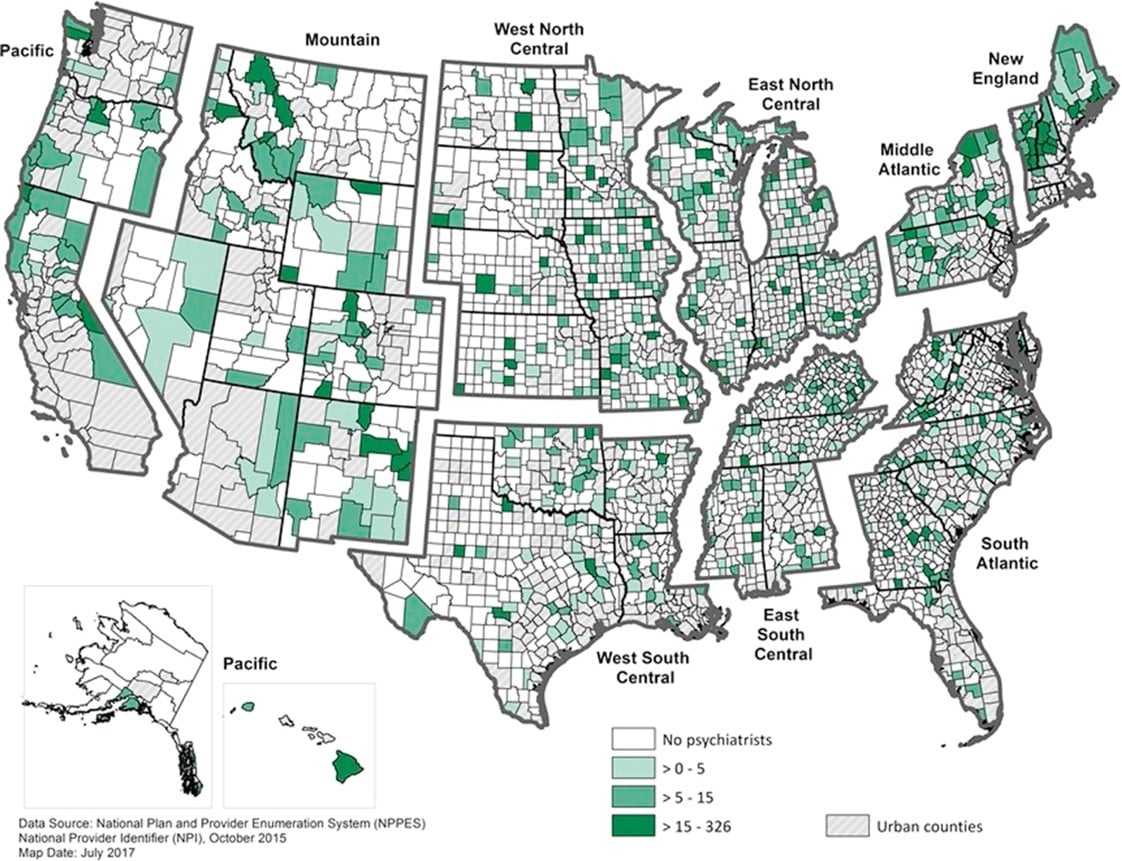

The problem is even more severe in rural America as the graphic below depicts where approximately 50% of counties in the US lack a resident psychiatrist, 65% of non-metropolitan US counties lack a psychiatrist, and 47% lack a psychologist. (Source: The American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Geographic Variation in the Supply of Selected Behavioral Health Providers)

Psychiatrists in Rural US Counties per 100,000 Population

Additionally, while the prevalence of mental health disorders is similar between urban and rural settings, the level of services is dramatically different due to:

- Accessibility: Rural residents frequently travel long distances to receive mental health services and are less likely to be insured for these services.

- Availability: Mental healthcare professionals are more likely to practice in urban centers, leading to chronic shortages of mental healthcare providers in rural areas.

- Acceptability: The stigma of needing or receiving mental healthcare is more prevalent in rural areas which creates an additional barrier to care.

Finally, the impact of COVID-19 on mental healthcare has been nothing short of staggering. Issues include:

- fear of the virus and its effects, particularly for at-risk family members,

- loss of stability and income occurring from loss of job, food instability and lack of social connections, the latter particularly among adolescents and young adults,

- quarantining’s long-term ramifications for both mental and physical health, and

- impact on people who had COVID-19, as 34% of COVID-19 patients are diagnosed with a mental illness within 6 months of contracting the virus (Source: WebMD, 1in 3 Have Neurological, Psychiatric Problems Post-COVID).

The Role of Primary Care Providers

With the increased demand for mental health treatment and lack of resources in America and in rural communities, specifically, primary care providers are increasingly being called upon to be the backstop for mental health services. It is normal to go to your doctor when you are not feeling well, and especially if primary care professionals are the only resources available within the community. But when it comes to mental healthcare, primary care providers generally lack psychiatric training, with the result being:

- Primary care physicians treat an estimated 60% of people for depression in the US and prescribe 79% of antidepressant medications, yet they lack the tools, training and time to successfully diagnose mental health issues. (Source: Collaborative Care for Depression in Primary Care: How Psychiatry Could “Troubleshoot” Current Treatments and Practices.)

- Primary care doctors are forced to rely on the screening tool assessments that they have at hand to help make a diagnosis. These screening tools are antiquated and one-dimensional, screening for symptoms or clusters of symptoms for a single disorder only. They lack the depth and breadth to properly identify mental health disorders. Not coincidentally, two of the most used screening tools, the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ9) for Depression and the General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD7), were funded by Pfizer who makes pharmacological treatments for both disorders.

Within that context, the misdiagnosis rates for various disorders are predictable despite the best intentions of the healthcare provider:

- Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) misdiagnosis is over 65%,

- General Anxiety Disorder (GAD) misdiagnosis is 71%,

- bipolar disorder misdiagnosis is over 92%,

- panic disorder misdiagnosis is over 85%, and

- social anxiety disorder misdiagnosis is almost 98% (Source of all statistics: Rates of Detection of Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care).

How to Move Forward with Technology

One thing COVID-19 taught us was that when pushed, people were willing to turn to technology to solve the increased need for access to quality healthcare and behavioral healthcare in particular. In March 2020, use of telehealth for psychotherapy jumped from historically under 5% to 68% of total behavioral health claims, and telehealth psychotherapy has remained high at 60% of all claims in March 2021. Also as of March 2021, people were 2.8 times more likely to visit a psychologist or psychiatrist via telehealth than primary care. (Source: McKinsey & Company Insights on utilization of behavioral health services in the context of COVID-19.)

With the US population being more willing to use digital technologies for behavioral healthcare than other healthcare, we have an opportunity to leverage digital technologies to design and implement a comprehensive digital behavioral health solution for our nation’s rural community health programs to replace outdated, inadequate, or non-existent solutions in these communities today. A digital health solution holds the promise of creating an advanced stepped care model that can:

- help address the inequity of patient care between rural and urban locations and improve accessibility and treatment for mental health problems in our rural populations,

- provide significant expansion of current community health resources and capabilities,

- provide technology extension of resources for a significant number of mental health disorders that today are not being treated, require long-distance travel for treatment, or are being misdiagnosed, and

- create a replicable, sustainable mental healthcare model ecosystem for our country’s rural community health ecosystem.

Here’s how it can work. At the point of patient intake – whether that is the community health center, attending primary care practice or clinic, a faith-based local service, or other health resource within the community – providers use behavioral health technologies from nView Health to screen and help providers assess a person’s mental wellbeing. These technologies primarily focus on a clinical series of digital tools including:

- short 3-5 minute screening solutions to test for multiple adult (17) and pediatric (24) DSM-V mental health disorders,

- structured 10-18 interviews to further analyze specific disorders for which the patient tested positive,

- complete documentation for the provider to assist in proper diagnosis,

- disorder-specific monitors that the provider can have automatically delivered to the patient at provider-prescribed intervals (daily, weekly, monthly), and

- a series of severity rating scales and cross-cutting measurements to further optimize the tracking and documentation of patient outcomes.

Once a patient has been properly diagnosed and a treatment plan is in place, any number of other digital technologies may be deployed to support the patient’s progress such as:

- full-service telepsychiatry and resources as required,

- online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy with structured videos and content,

- social media applications integration to monitor patient behavioral health actions and alerts,

- Physio-behavioral health monitoring applications to monitor patient actions and alerts,

- genetic testing to assist in precision treatment with behavioral health medications,

- integration to existing or implementation of patient engagement and/or electronic medical records systems, and

- home delivery for prescription medications for behavioral health conditions.

A coordinated, digital technology platform such as this can be achieved today to advance behavioral health and fulfill the future requirements for measurement-based care standards. Most importantly, technology provides a new and correct course of action to better serve the behavioral health needs of our rural and frequently most vulnerable population, providing significant and sustainable value to the patient, the provider, the community, and the nation.

.png)